Press. voanews.com.

While we may not

get to that earth-like planet around Proxima Centauri anytime soon, NASA

scientists are proposing all kinds of ways to explore the planets, moons,

asteroids and various other rocky and icy things floating in and around our own

solar system.

Checking in at

the NIAC Symposium

The plan to head

to Titan was laid out at NASA's annual Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC)

Program Symposium held this week. The NIAC program is intended to fund

visionary ideas that go way beyond things as mundane as going back to the moon

or putting a colony on Mars. In fact, some of the ideas on display seem like

science fiction, but this is all real, and while the missions and concepts can

boggle the mind, they show just how deep into space NASA is looking.

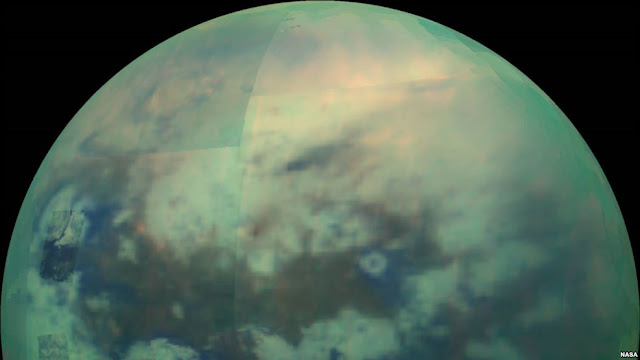

But first, a bit

about Titan. It's the second largest moon in our solar system, behind Ganymede,

which orbits our largest planet, Jupiter. It is a beautiful moon, at times

looking positively earthlike with its cloud-filled skies. It is unique in that

it has a dense atmosphere composed almost entirely of nitrogen with clouds of

carbon-rich methane and ethane. Its surface is mostly ice and rocks. We only

learned that in 2004, when the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft got close enough to

peer through the yellowy nitrogen-carbon smog.

But Cassini also

found liquid on Titan -- a lot of it, in the form of giant lakes of

hydrocarbons. In fact, according to Jason Hartwig from NASA's Glenn Research Center,

Titan is “the only other body, other than earth in our solar system, that has

stable accessible seas.” Hartwig is part of the team, called COMPASS, that NASA

funded and asked to figure out a way to get to Titan and explore its great

lakes.

Titan? Yes

Titan!

There are three

main seas on Titan -- Punga, Kraken and Ligeia Mare -- and together they are

about as large as the Great Lakes here in the U.S. They are composed entirely

of hydrocarbons, primarily methane and ethane. Hartwig says that's “about 100

times more liquefied natural gas on Titan than the whole planet earth

combined.” Exploring those seas, seeing what's in them, and perhaps more

importantly, what's at the bottom of them, is what NASA's Titan Submarine

project is all about.

That's right. Submarine.

Team leader Steve Oleson, along with Hartwig and the rest of the COMPASS team,

wants to send an autonomous submarine to Titan that would roam around, up and

down these giant lakes. They have a proposed launch date of 2038, a 7-year

transit time and then a full year of this as-yet-unnamed sub cruising around on

Titan. Why 2038? That's to make sure Saturn doesn't get between Titan and the

earth, so NASA can talk to its little explorer.

Details,

details, details

The submarine

will be about 6 meters long, equipped with a small plutonium engine in the back

called a Stirling radioisotope generator (SRG). The heat from the engine keeps

the electronics in the front of the sub warm. That's vital because the

hydrocarbon seas are a frigid minus 180 degrees celsius.

And the sub also

has a potentially retractable sail that runs along its length. After 8 hours

under Kraken Mare, it would resurface, Hartwig says, "and have 16 hours to

communicate and recharge and all that." From a layman's point of view this

may seem a bit like a thought exercise. And to some extent it is. But so was

going to the Moon until we did it. The level of detail that the team has

drilled down to makes it clear they think this is something we can actually do.

One strategy

they've put together to make this real is an exercise called a COMPASS run.

Hartwig calls it "very intense." Basically, he says, "it's a

bunch of people sitting together for 4 - 5 days straight trying to update the

design." They bash through every

imaginable problem. “We are finding that the terrain around some of these seas

is really quite treacherous,” Hartwig explains, so if the sub is, for instance,

piggybacking on a probe that is exploring Titan's surface, they have to make

sure it's sturdy enough to get to the water's edge. The more likely scenario is

for the sub to be dropped directly into Kraken Mare from low orbit for a safe

submarine splashdown.

Another COMPASS

problem? Bubbles, caused by the hot sub hitting the cold hydrocarbons.

"That waste heat we’re dumping into the liquid may be enough to cause

bubbles," Hartwig says. Those bubbles can get in the way of cameras or

even "coalesce at the aft end and cause our propellers to cavitate,"

which could stall the sub in the water.

Whether the

project actually happens though is still uncertain, NASA has a notoriously

tight budget. But it's fun to realize that we are in fact capable of achieving

such an audacious voyage of discovery.

:::::::::::::

Donate Now With Web Site Senderos de Apure.

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr?cmd=_s-xclick&hosted_button_id=J56SNTP4DS5UY

.jpg)